LOST

Almost two dozen homeless men and women died last year in Hillsborough. Who were they? How did they fall so far?

TAMPA

A white van comes for the homeless who die in Hillsborough County. It is unmarked and unremarkable, a dignity for those whose lives ended with little of it.

The van carries each body to the Medical Examiner's Office, a brick complex not far from the thrill-screams of tourists riding roller coasters at Busch Gardens. By law, the medical examiner investigates any death that is violent, unexpected, suspicious or unattended. The ones who die with nothing or no one end up here.

Inside, the smell is antiseptic with something heavier underneath. The body is wheeled across clean terrazzo floors. An autopsy tech in blue scrubs pecks at a laptop, filling in blanks.

Homicide. Suicide. Fall, the final forms will say. Alcohol. Overdose. Hit and run.

The tech works methodically, soft ’80s rock playing in the background. Each body is weighed and a toe tag attached. He lifts lifeless hands to be inked for fingerprints that will say who they were.

The bodies are wheeled into a walk-in cooler to await an autopsy and then cremation at taxpayer expense — $345 for an adult, $120 for a child. If no one comes to claim them, there will be a lonely burial at sea.

•••

In 2017, 22 people died in Hillsborough County with nowhere to live — part of an entrenched population of homeless who sleep in cars, panhandle street corners, stay in shelters, eat at soup kitchens and get arrested for minor crimes over and over. It is a death toll that rarely makes headlines.

But who were they, the people whose eyes caught yours for a few seconds over a cardboard sign that said “homeless, hungry, please help?” Who had they once been? How did they fall so far?

The Tampa Bay Times spent a year chronicling the lives of Hillsborough’s homeless dead, tracing their paths backward to when they were someone’s child, lived in a house, slept in a bed.

Autopsies noted long-healed broken bones and fresh bruises, tired livers and overburdened hearts, scars and tattoos — clues to a life lived. But even more was revealed through dozens of interviews and hundreds of records:

- A majority of the dead were white men. Five were women, two were black, one was American Indian and four were Hispanic. Four were military veterans. Their average age: 51.

- Some burned family bridges long ago. But at least half had relatives living in Hillsborough, often within a few miles. Nearly half spoke to relatives regularly and even visited them while living on the streets.

- Two who died homeless left behind a twin. Each of the surviving siblings has a stable life — a home, a job, a family.

- Alcohol abuse was a common thread for a dozen who died. Drugs were another. Opioid painkillers, methamphetamine, cocaine and spice — a cheap, synthetic marijuana — were part of the lives of nearly half the dead.

- Lack of health care — including mental health care — was a major factor. So was the brutality of life on the street. Half succumbed to liver disease, heart disease, blood clots or cancer. Two were hit by cars, one by a train and one drowned. Two were dead so long before anyone noticed it was impossible to say what killed them.

- Half were homeless by choice, so-called “chronics’’ who resist help. Non-profits fed them and they got spending money from government checks and strangers who handed them crumpled bills — acts of generosity some say only makes it easier for diehards to stay on the streets.

- Among the dead: a security guard, steelworker and professional saxophonist, even a successful doctor.

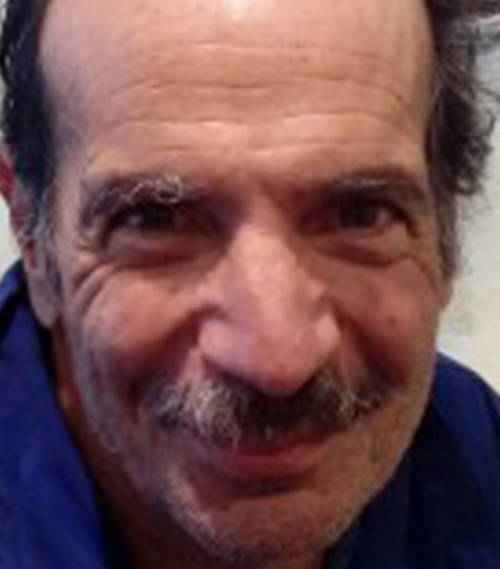

Consider the rise and fall of Dr. James P. Oakes.

Oakes served in the U.S. Air Force, got his biology degree from California State University at San Bernardino and became a doctor of osteopathy in Tampa and Pinellas. Friends say he was fiercely bright, intense, even manic — big voice, big smile, big opinions. Tattooed on his backside was a heart with a halo. He did not lack confidence.

He worked out religiously and weighed 200 pounds of “brick, not butter,” said his former wife Sarah Gordon. Home was four-bedrooms, four-baths on the water in Apollo Beach.

He had another side, accused of domestic violence by three of his four wives. Gordon said he had used steroids but gave them up.

Around 2009, he decided he didn’t want to be a doctor any more. He got hooked on the stock market and spent up to 20 hours a day trading on his computer. He lost friends, weight, and finally, the family fortune.

In 2011, Dr. Oakes tried to sell three suitcases of oxycodone — 10,000 pills — for $67,500 to an undercover cop.

In jail, he fasted himself nearly comatose and called his public defender Satan. He pleaded guilty, was sentenced to 51 months in federal prison and ordered to get mental health and drug treatment when he got out.

When he did, he was no longer a doctor. He didn’t even have a car. While he was living at a housing program for the homeless in 2015, he was charged with hitting a nurse, found incompetent and sent to a state hospital.

Back in jail in 2017, he fell out of his bunk and soon after died from a blood clot. He was 55.

“That’s a long fall,” said Jack Gordon, a local attorney who had been his friend. “A long fall.”

•••

Robin Swoveland and Richard Wiseman were living proof that a strong desire to work is no guarantee you won’t fall off the grid.

They met in small-town Indiana where both got jobs with the railroad driving to pick up engineers after a run to Cleveland or Kokomo. He had served 23 years in prison for bank robbery. She was his U-turn.

She told him she’d been kicked around since she was little and left behind a divorce and two kids. She said he didn’t have to be like he’d always been. “I guess that’s maybe one of the greatest things Robin ever did,” Wiseman told the Times. “Teaching me to be happy.”

In Las Vegas he opened a carpentry shop and she worked as a security guard. She loved the uniform, the responsibility. They had an apartment, car, bills paid on time. Once, she made enough on the nickel slots to pay a month’s rent. “We were so happy there,” he said.

It all fell apart in 2007 when they became statistics in the Great Recession that would kill nearly 9 million jobs, including theirs.

With their last $5,000, they bought a used motor home and headed to Tampa, where Wiseman had worked at the Borden dairy as a teenager. Their little white dog, Ruff, rode on the cooler that was their refrigerator.

They arrived in a city so changed they got lost, the dairy long gone. They stopped in a parking lot behind a Sweet Tomatoes to figure out what to do next. It was home for three years.

Some days, Swoveland stood by the road outside a Best Buy holding a sign that listed her years as maid, landscaper, child care worker. Help me please. I need some gas money, find a job. No beer or drugs. God Bless You, her sign said.

She tried to ignore the ugly things men said. On a good day she could make $85, enough for a motel and a hot shower.

‘Homeless can happen to anybody...’

Wiseman got work as a motel maintenance man and Swoveland found a security guard job. With paychecks and a combined $270 in monthly welfare benefits for groceries, they moved into a $660 a month mobile home. At Goodwill, she bought a tiny Christmas tree and a wedding dress that fit her perfectly. They were doing okay. Then she started to limp.

A clinic sent her to Moffitt Cancer Center. While they were trying to figure out what was wrong, an eviction notice went up on the trailer. Their belongings were strewn outside, and by the time they got to them, her wedding dress was gone. Now their Ford Taurus was home, him sleeping in front, her in back. They parked near a Wawa for bathrooms and under a sprawling oak by a Walmart for shade.

The next doctor put her in the hospital. Cervical cancer, they said — often preventable and treatable. But like many homeless people, Swoveland had no insurance and not much contact with doctors. Her case was advanced.

She had missed a deadline applying for Medicare. He asked if she could use his Medicare, but they said it didn’t work that way. He found an insurance policy, $30 a month, but she had a pre-existing condition, a term he grew to hate. Swoveland, 59, moved from hospital to hospital to a Salvation Army medical bed. He traded the car for a van with the back seats removed so she could lie down.

After Christmas they explained hospice care to him, how it would be better if she died peacefully instead of being rushed to the next hospital. She told him she loved him. She said she was scared. Just before 10 a.m. on Jan. 18, she died under crisp, clean sheets with a morphine drip in her arm and the love of her life holding her hand.

•••

Daniel McDonald, a homeless liaison officer with the Tampa Police, doesn’t believe anyone wants to be out there. But some people get used to it.

“I think resilience is one of our greatest assets,” he said. “And our greatest weaknesses.”

Richard Stubbs chose a life without walls. He was a pretty good guy growing up, his sister Lisa Winkelpleck said, but he started getting in trouble, stealing and using drugs. He was a talented artist but didn’t do much with it. He dropped out in 11th grade and got his GED.

Their father was a jail deputy. When his son got arrested, he knew it. “That broke my dad’s heart,” she said.

Over the years, Stubbs did stints in state prison for burglary and grand theft. In recent years, he mostly got arrested for panhandling and trespassing, crimes of the homeless.

Winkelpleck and her husband gave him money but he didn’t want help coming in from the streets. At one point, she said, her brother was hit over the head and knocked unconscious. After that he wasn’t the same.

One day he showed up at Trinity Cafe, where anyone hungry is served a hot meal. He’d been a favorite volunteer there for years, riding his bike miles from his camp near MacDill Air Force Base to tie on a white apron and bus tables. Now people at Trinity saw he was shakier, weaker, not as clean, not as articulate. Now he didn’t offer to work — just came for a meal like anyone else.

Just after 1 a.m. on a Friday in February, a man named David Franklin and his wife were headed home on Gandy Boulevard after watching the Tampa Bay Lightning lose and then a stop at the I Don’t Care Bar.

A figure in dark clothing limped out into traffic. Franklin’s pickup sent the man flying. Scattered around him were his dirty ball cap, flashlight and left Nike sneaker.

A 21-year-old veterinary student got out of a car to help. She felt the man’s faint pulse, tilted his head to clear blood from his mouth. She held his hand as paramedics arrived and started working on him. He squeezed her hand again and again until the ambulance took him away.

Franklin was arrested and charged with misdemeanor DUI. Fingerprints taken at the medical examiner’s office identified the dead man as Stubbs, who had been living under a Crosstown Expressway overpass nearby.

Nine months later, Franklin stood before a county judge and pleaded no contest to a reduced charge of reckless driving. He got 12 months’ probation. There was no mention of Stubbs. The judge was not told anyone died.

Franklin later left a voicemail after a reporter contacted him: All I can say is, you know, I feel horrible about what happened to the gentleman. I still even have nightmares about it.

Stubbs’ sister brought his cremated remains home. “He’s not suffering anymore,” she said.

•••

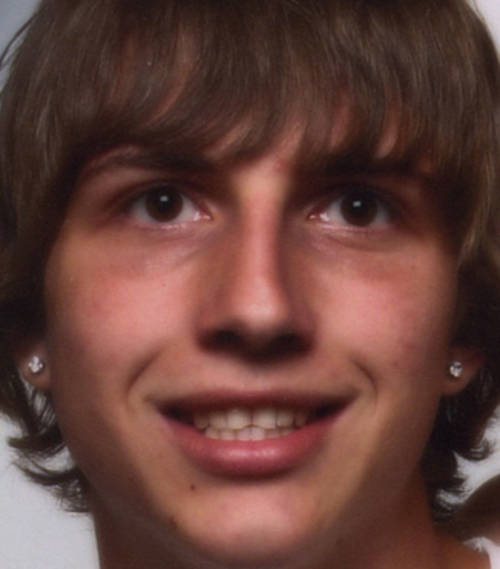

Jan Clausen knew if his son had a prayer of beating his drug addiction, he would first need nowhere to go but up.

“Sometimes, you have to hit your bottom,” said Clausen, a self-employed metal scrapper who lives in rural Seffner. “But his bottom was death.”

Wade Lemar Clausen, 27, became the youngest person to die homeless in 2017 when he hanged himself on Christmas Day.

Handy with engines, his son had wanted to be a mechanic. When Wade was at Armwood High, his father made him a promise: Graduate and you get your grandfather’s Jeep, gray with precious few miles on it. In 2008, after Wade was handed his diploma, his father handed him the title.

Wade was working on the Jeep’s suspension, torquing hard on a wrench, when he hurt his back. Later, he would tell his dad how a girl at the restaurant where he worked as a cook gave him a little blue pill, how she showed him to crush it in a straw and then snort it so it didn’t hurt to be on your feet all day. Back then, his father had wondered about all those mangled straws he kept finding around the house.

“And that was how his addiction started,” he said.

When Wade got a job doing duct work at Tampa International Airport, his father encouraged him to stick with it, turn it into something steady. Instead, Wade and his longtime girlfriend bought a Chevy truck with tax refund money and started a hauling and moving business, his father said. They had two children together.

“Sometimes he was happy, way out there,” his father said. “That’s probably when he was higher than hell.”

The drugs got worse. Their small children lived with her family. They were losing everything, his father said.

Wade admitted he was taking three pills a day, $20 a pill. His father could not fathom how he afforded this. He was “banging” — crushing and dissolving them in water and shooting up. He was trying methamphetamine to get off the opioid painkillers at the center of a deadly nationwide drug crisis. He was sinking.

On an August evening, a sheriff’s deputy knocked on the window of a green Ford Ranger parked at the Thonotosassa public library. According to the report, Wade opened the door and the deputy saw a plastic container sticking out of his shorts pocket. It held a small red straw and a little blue pill the deputy recognized as oxycodone. Clausen was charged with possession of a controlled substance without a prescription, a felony.

In court, he was deemed eligible for an intervention program that would mean drug treatment instead of a trial. His father thought it might save him. He almost had him talked into it.

‘His bottom was death’

But Wade said the lawyer told him he could fight the charge by arguing illegal detention and search. “Denies drug problem,” said a note on the docket.

Before Christmas, Wade and his girlfriend came by his father’s house. His dad, sober 18 years, tried to talk about what he’d learned in Alcoholics Anonymous. “I was trying the tough love thing,” he said. It was the last time they saw each other.

On Christmas Day, he and his girlfriend argued, she later told investigators. The last thing he said was he wasn’t coming back. For two days she tried calling him, then went looking for him in the woods behind the Seffner Walmart where they had camped together when they were homeless. Over a carpet of brown leaves, he had used a dog leash to hang himself from an oak. Amongst his belongings detectives found a needle-less syringe.

His father raced to the scene to see him, but a deputy stopped him. It was a kindness. “I didn’t want that to be my last memory — no,” his father said. “I could handle a total stranger. But not my own son.”

Afterward, he talked about how big drug companies making big profits should pay for the recovery of people struggling like his son. He went back to the woods behind the Walmart. Deep in the oak’s trunk, he carved his son’s name, along with a cross.

•••

Death investigators from the medical examiner’s office are usually able to locate next of kin, even for the homeless. Sometimes relatives pay for burial or cremation. But sometimes, even when family is found, no one comes for them.

When the weather is right, urns are loaded onto a fishing boat behind the home of John McQueen of Anderson-McQueen funeral homes in St. Petersburg. The unclaimed sit next to the ones whose families paid to have them scattered at sea, treated no differently. They speed past the downtown skyline and curve out to the Gulf of Mexico. Some days dolphins lead the boat.

Bailee McQueen, a University of Tampa student, makes the trip with her father when she can. By law, they must go out at least three nautical miles. They travel five, positioning the boat due west of the pink Don CeSar resort hotel so it can be a landmark if friends or family ever show up and ask.

McQueen cuts the engine, and it’s suddenly quiet except for waves lapping at the hull. They bring the urns out one by one, each containing a plastic bag that weighs five pounds or so. Bailee McQueen says something to each of them: “I’m sure your family would want you to know you would have been missed.”

And then to another: “I’m sure you graced this world with a lot of beautiful things.”

The remains are poured over the side of the boat, each forming its own distinct cloud in the water. They drift away, following each other out to sea.

“Goodbye,” says a young woman who never knew them.

By the numbers

2017 Hillsborough County homeless deaths

- Five women, 17 men

- Four were military veterans

- Nineteen were white, two were black, one was Native American

- Four were Hispanic

- Six immigrants (from Cuba, El Salvador, Honduras, Jamaica, Morocco) Their legal status could not be determined.

- Two had twin siblings (both have jobs, families and homes)

- More than half had family members living in Hillsborough County

- Half received shelter or mental health/substance abuse services through local agencies

- Half fit the HUD definition of “chronically homeless”— continually homeless for a year or more, or experienced homelessness four or more times in the last three years with the four episodes totalling 12 months or more.

Breaking the cycle of homelessness

Homeless deaths

- Oldest — 65

- Youngest — 27

- Average age — 51

Causes of death

- Alcohol-related (liver cirrhosis, chronic alcoholism) — 5

- Blood clot — 2

- Body too decomposed to determine cause — 2

- Cancer — 2

- Drowned — 1

- Heart Disease — 5

- Overdose — 1

- Struck by car — 2

- Struck by train —1

- Suicide — 1

More on Hillsborough's homeless

About the reporters

Additional credits

- Editor Barry Klein

- Photo editor Boyzell Hosey

- Video production Danese Kenon and James Borchuck

- Story design Lyra Solochek and Lauren Flannery

- Contributing writers Libby Baldwin and Howard Altman