Walmart

“What did you think this job was?”

She doesn’t want to do this. “Not. At. All. I’m not ready,” she tells the other cadets.

They’re wearing their uniforms, ties and shiny shoes, finishing lunch on this Friday in late October. They’re getting ready to move onto the next assignment at the St. Petersburg police academy: Interviewing.

“I don’t know what people are going to say. If I’m shopping, I don’t want people bothering me. Especially a cop,” she says. “Especially now.”

Brittany “Mama” Moody rarely complains.

Not when she got punched in the face during boxing, or kicked in the shin during a take-down, or thrown on her stomach and handcuffed.

But she’s been dreading this day: The recruits must talk to strangers.

“Is someone going to hit us?” Moody asks. “Will we have to use our defensive tactics?”

For some people, this part is easy. Much better than having to run 1.5 miles in 100-degree heat, learn dozens of legal definitions or tackle a suspect on a gravel road.

Moody sees it as torture.

Coach Joe Saponare laughs at that. What did you think this job was? Most of your time, you spend talking to strangers. You gotta get used to this.

It’s generational, he says. When he was coming up 30 years ago, people still talked to each other. Face to face. All the time. And phones were not for texting.

Some of these millennials — or are they even younger than that, Gen Z’s? — anyway, they don’t talk even when they’re in the same room, Coach Sap says.

“It’s getting worse every year,” he says. “That’s why we got to get them out there, practicing their communication skills.”

Six weeks into their training, Class 219 has lost six recruits. One’s infant got sick. Someone caught COVID.

The 24 who are left have learned how to fall and break falls, the difference between an interview and an investigation, how to holster a gun, approach a burglar, take fingerprints, collect evidence and handle a body when its skin is stuck to the floor.

All but four already have been hired by local agencies. Everyone except the youngest is keeping up with the physical training. That affects them all. When one person doesn’t pump enough push-ups, they all have to start over. Cadets started making the 19-year-old work out at lunch, KeVonn Mabon drilling him as if he were training for the NFL. While others eat at the long tables, Mabon counts squats and sit-ups.

“I’ll talk to anyone,” Mabon says that Friday as they clean up after lunch. He turns to Moody. “You got this.”

Take really good notes, a coach tells the cadets.

“Notice tattoos and piercings, write those down. After the interviews, you’ll all be up here at the podium reporting back to us. So make sure you can read your notes. Get quotes. They have to be direct quotes. Get their first and last name and occupation. Use small notepads, don’t open your laptop in front of them.

“Avoid generalizations. Ask follow-up questions. What does that mean? Every call you go on, you’re going to meet two or three people, at least. And you’ll have to talk to all of them. You can’t be shy.”

Surely some of you have been face-to-face with strangers before, the coach says. “What other jobs have you had?”

Security. Dog track. Receptionist at a chiropractor’s office. Army. Marines. Cable guy. Server.

“You have to explain quickly why you’re out there, what you want,” the coach says. “Anybody have the heebie-jeebies?” Half the class raises their hands. “Just work through the fear. Today, our mission is to find out what their perception is of law enforcement officers.”

Someone groans. Others exchange glances. Moody hangs her head.

“If they’re anti-law enforcement, ask: What can I do to change your perception?”

He projects a map of Walmart on the screen behind him. It’s right across the street from the police academy. “Try to get people approaching as opposed to leaving. They might want to get their groceries home. Don’t go inside Walmart,” he says. “And remember your interview stance: feet shoulder-width apart, gun leg back. Be nice. Be human. Try to make a connection. If someone gets in your face, back off.”

Moody doesn’t have a notebook. Mabon needs a pen. They team up, and stake out a spot by the garden center.

“Excuse me, Sir,” Mabon calls to a middle-aged Black man walking through the parking lot. The man doesn’t stop. Mabon catches up to him. “Can I ask you a question?” The man shakes his head. The next woman does the same.

“We should’ve gone to Publix,” Moody says, “where people are happier.”

It’s hot in the afternoon sun. The air smells like asphalt. The cadets are sweating in their long-sleeve dress shirts and polyester pants. “Excuse me, Ma’am,” Mabon says, approaching an elderly Black woman. “I just want to get your opinion on law enforcement.”

“Well, that’s a big topic,” says the woman. “You mean, locally?”

“How do you think the officers who’ve been deemed bad can be better?” asks Mabon.

Police need to get out into the community, she says. Build relationships. Know who they serve. “Yes, Ma’am.” And you have to train them so their response isn’t excessive, she says, make them show some respect. “Yes, Ma’am.”

And you’re in danger, too, she tells him. Protect yourself. Protect your partner, she says. “Thank you, Ma’am.”

Moody puts on sunglasses, watches people slide by, gears up for rejection. When a Black man wearing a Vietnam vet ball cap nods at her, she nods back. “How you doing, Sir? Can I ask you a question?” The man stops. “I just want to get your opinion on law enforcement.”

“I tell you what,” says the man, chuckling. “It’s a whole lot different than when I was in law enforcement.”

“Oh, you were in law enforcement?” asks Moody.

“Yep, 23 years, retired now, from Washington, D.C.”

“That’s where I’m from!” Moody says. “Well, I’m from Baltimore.” For the first time all day, she smiles.

She has wanted to be a police officer since she was 7, her son’s age. Her dad is a security guard at George Washington University, and as a girl, she loved watching him put on his uniform, felt proud that he protected people.

“I wanted to do that,” Moody said. “Help people.”

Moody’s parents were high school sweethearts, and she and her older brother grew up with them coming to her volleyball, softball, soccer and basketball games. She was 10 when they split up, which “took a huge toll on me,” she said. Her mom worked at the post office and took a transfer to Tampa when Moody was in seventh grade.

In high school, Moody played sports, studied karate, hung out with kids who hated cops. Her grades started slipping, she was acting out, getting in trouble.

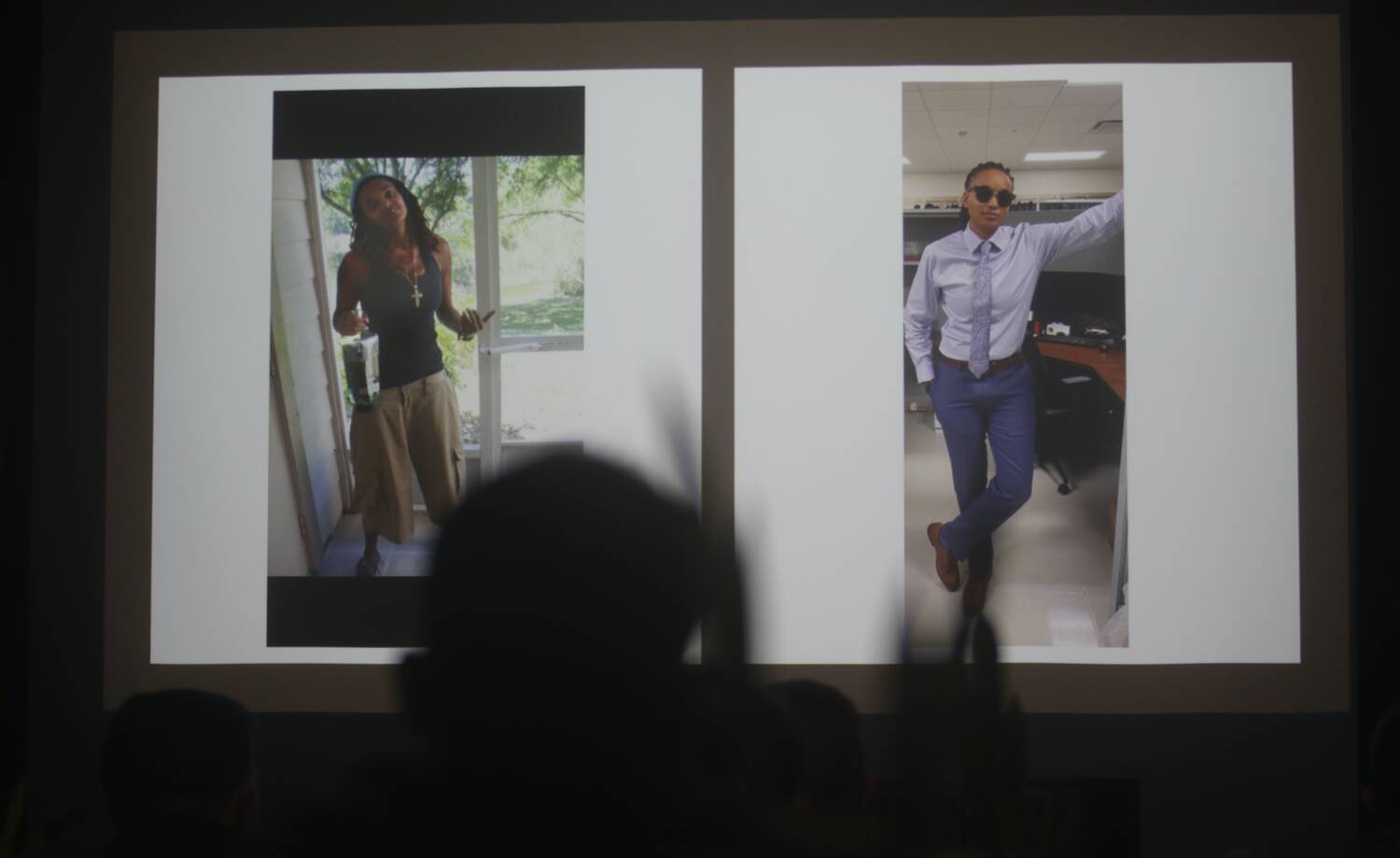

During a presentation at the academy, she showed a photo of her back then — wearing a sleeveless navy undershirt, baggy khakis slung below her hips, a big, gold cross necklace. Then she showed a photo of her in shirt and tie. She talked about perception, how she’d had to change and cut off everyone around her, shut down social media. “You are what you put out into the universe,” she said.

At the University of South Florida, Moody studied criminal justice but didn’t get her degree. She worked at Burger King, Cold Stone Creamery, Ikea.

Her son was born when she was 23.

He was a surprise; his dad is her best friend; they met bowling. They co-parent from separate homes. Now, she said, “we’re like brother and sister.”

After Bryan was born, Moody decided it was time to pursue her passion. She applied to the academy, sailed through the physical tests but failed the written entrance exam. Twice. So she took a job at the Pinellas County Sheriff’s Office handing out uniforms, learning what deputies do.

Finally, last summer, she was accepted into the academy — and the Sheriff’s Office sponsored her. If she graduates, and passes the state exam, she’ll be a deputy.

“Just because you fall down doesn’t mean you stay down,” she said.

Moody lives in a townhouse in Brandon with her girlfriend, her girlfriend’s 12-year-old son, her boy and a friendly pit-bull mix named Maggie. Every morning, she gets up at 4 a.m., drinks a protein shake, packs lunch, meditates, then carries her sleeping son to her truck and drives to her mom’s house. She eases Bryan into bed beside his grandmother about 5:45, kisses him good-bye, then drives another 45 minutes to the academy to run three miles and do Crossfit training with Coach Sap.

After all day at school, she picks her son up and heads home by 6:30. Except twice a week, when she takes Bryan to basketball practice at the YMCA. She helps the second-graders warm up, running drills and rebounding their shots. When practice starts, she sinks into a folding chair on the far side of the gym and takes out her basic training textbook, highlighter and flashcards.

“I’m super exhausted all the time,” she said. “But there’s no doubt in my mind that I want to do this.”

She doesn’t want Bryan to be scared of cops. She wants him to know they are here to help.

Moody’s mom, Stephanie Johnson, said she was surprised when her daughter told her she wanted to be an officer, “especially in light of all the stuff going on right now.”

“She’s a Black female with alternative sexual orientation, raising a small son. I told her, ‘How many more things do you want stacked against you?’ But she won’t entertain a negative comment about what she’s doing. She’s very driven. And stubborn.”

She doesn’t test well, her mom said, but she’s a good leader. “She’s going to impact lives, change perceptions. The Sheriff’s Office is lucky to get her.”

Of course, Johnson is worried. She’s a mental health counselor now, well aware of the psychological, as well as physical risks, police face.

Once her daughter is on the streets, Johnson said, “I’m going to have to be on prayer all day.”

In the Walmart parking lot, the man in the Vietnam vet hat asks Moody about her dad’s work in security, how long she’s been at the academy, how she’s doing. She does most of the talking.

Then she remembers her assignment. “So you said law enforcement is a lot different than when you were in it,” she says. “How?”

The man strokes his white beard and says slowly: “People in policing now, they come from an environment of bullying. They need training, someone to teach them to help and be kind.” Moody races to write down his words. “And when the police break the rules,” the man says, “you have to hold them accountable.”

They talk a little more, and Moody thanks him “so much” for his time. “I hope things will change with training, and whatever else it takes,” she says.

“Good luck to you,” says the man.

Back in the classroom, the cadets compare notes. Some shoppers praised law enforcement, or had officers in their families. Many refused to talk.

A nurse told one recruit that to some people, her Black teenage son looks like a thug. But he isn’t. “Don’t be too quick to judge.”

Instead of arresting autistic kids, cops need to learn to talk to them, a teacher said. A cafeteria worker told a cadet, “Don’t be trigger happy.”

Moody tells classmates about the man she met. She was supposed to talk to at least two people but only interviewed him. “He said police need to grow up and take responsibility for their actions or fire them,” she says. “A lot of officers are getting in trouble and nothing’s happening.”

A youth counselor told a female recruit that sheriff’s deputies have always been rude, then called her a “paramilitary a--hole.”

“So what have we learned today?” asks the coach.

Nothing they didn’t already know: Lots of people hate cops.

It’s good to keep that in mind out in the field, when a suspect is holed up in a building, and you’re the only thing between him and jail.